50th ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION OF TINKER

The community is invited to a reception celebrating a half century since the U.S. Supreme Court’s Tinker decision, protecting the free speech rights of students.

The event is Sunday, February 24 beginning at 2:30 PM at Harding Middle School.

You’re flipping through the winter issue of the Hoover High Challenger. The usual stuff of life in the teen ages: stories on Pep Club, senioritis, the state speech contest. Then you turn to Page 16 and are blindsided by a headline you don’t expect to see in a high school publication:

WHAT COMES AFTER THE AMERICAN DREAM IS CRUSHED?

The story recounts the struggle of a family decimated by the deportation of its irreplaceable father/husband/breadwinner.

Senior Maria Gasca wrote it about a classmate’s family, but her own father recently returned to Mexico when his application for a Green Card that confers permanent residency was denied.

Des Moines is hundreds of miles from America’s southern border, but many DMPS families are trying to strike a delicate balance along a razor’s edge between countries.

Student publications in the district haven’t always been so forthright in their coverage of controversy, partly because it isn’t always walking the school halls, but also because they weren’t always free to be.

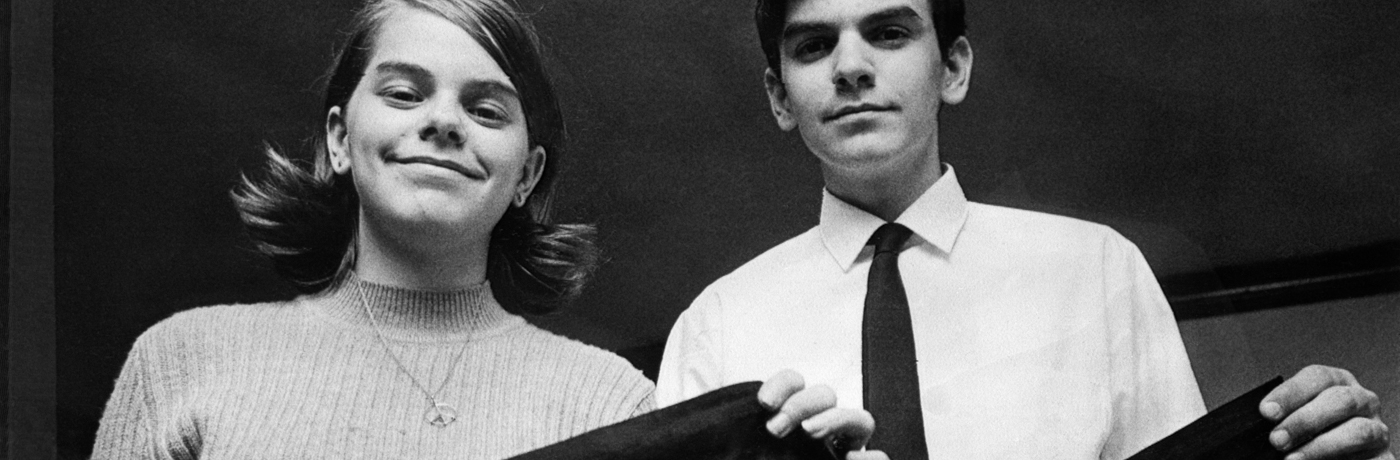

Next week, former DMPS students John and Mary Beth Tinker return for a series of events marking the 50th anniversary of the landmark US Supreme Court ruling in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District. The majority SCOTUS opinion in that case decreed that students don’t “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”

The decision was the culmination of a case that arose from a handful of DMPS students, including the Tinkers, wearing black armbands to school in December of 1965 as a means of silent, peaceful protest of the Vietnam War.

The background of the stand they took included a story written by a Roosevelt High School student in his journalism class and submitted for publication in the Roosevelt Roundup, the school newspaper.

The article would have raised awareness of the protest, which was in support of a Christmas Eve truce in the war advocated by then US Senator Robert Kennedy. It would have encouraged students to participate and to fast on a designated day in mourning for all of the lives lost in the war.

But instead of publishing the story, the journalism teacher referred it to the school principal who shared it with his counterparts at the other district high schools and district administrators. The school board got involved. The story never made it into print.

“All state and federal laws regarding the publication of student materials shall apply, and the Challenger will not publish materials which…are deemed libelous, obscene or a material and substantial disruption to normal classroom activities. The views expressed are not those of Des Moines Public Schools faculty, staff or administration…” reads the disclaimer that runs in every issue of the Challenger.

The highlighted phrase harkens to a threshold established by Justice Abe Fortas, who wrote the majority (by a resounding 7-2 vote) opinion in Tinker v Des Moines.

“The justices considered it significant that armbands had been forbidden only after a student…had wanted to publish an article about Vietnam in the school newspaper,” wrote Stephanie Sammartino McPherson in her book Tinker v Des Moines and Students’ Right to Free Speech.

Times have changed.

“As advisors, we don’t dictate any of the content of the newspaper or yearbook. Our student editors decide what to print,” said Sarah Hamilton who teaches journalism at Hoover and advises the Challenger staff. “Iowa is one of a handful of states that remain committed to the Tinker standard, versus the Hazelwood ruling*, and allow students the right to free press. Once I start dictating what the students write, it becomes my paper versus their paper. Our journalism curriculum at DMPS, which we journalism teachers wrote, includes an ethics and professional responsibility standard based upon Society of Professional Journalists ethics. We work to instill these concepts into our student journalists.”

The story Maria Gasca wrote for the 2018-19 Hoover High Challenger shared some bad news. But it’s a good thing that she was allowed to share it.

It hasn’t always been that way.

* A 1988 SCOTUS ruling in Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier allowed for administrative censorship of student newspapers under certain conditions.