“So, how would you describe your marriage? What happened?” Every time someone asks about my marriage, or about my divorce, I pause for a moment. Inside that imperceptible pause, I’m thinking about the cost of answering fully. I’m weighing it against the cost of silence.

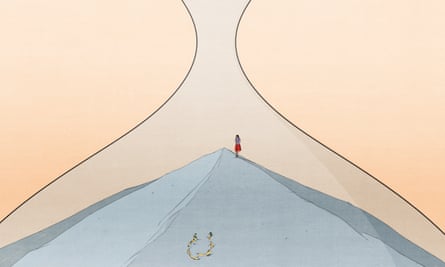

– I could tell them about the postcard I found in my husband’s work bag, addressed to a woman in another state, a place he’d been visiting for business. I could tell them how much I’ve spent on lawyers, or how much I’ve spent on therapy, or how much I’ve spent on dental work from grinding my teeth in my sleep, and how many hours I sleep, which is not many, but at least if I’m only sleeping a few hours a night, then I’m only grinding my teeth a few hours a night. I could talk about how a lie is worse than whatever the lie is draped over to conceal. I could talk about what a complete mindfuck it is to lose the shelter of your marriage, but also how expansive the view is without that shelter, how big the sky is –

“Sometimes people just grow apart,” I say. I smile, take a sip of water. Next question.

In 2015, three years before I knew my marriage was over, I sat in a coffee shop and wrote a poem on a legal pad, which is where most of my poems begin. It began, “Life is short, though I keep this from my children” and it grew into a piece about the fears and hopes I have for my children, and the complicated world I brought them into, equal parts terrible and beautiful. I titled it Good Bones.

The poem was published online in the journal Waxwing the following June – the same week as the Pulse nightclub massacre in Orlando and the murder of MP Jo Cox in England. The poem went viral. Reporters emailed, messaged me on social media, called.

Meanwhile, I was parenting two children, ages three and seven. I was their mom most of all – that was how I was known to people in my life, and that was fine with me. Even after the poem went viral, I was still hidden, cleverly disguised as one of the least visible creatures on Earth: a middle-aged mother.

I felt that my husband treated my (writing) work like an interruption of my (domestic) work. My occasional travel had been a sore spot in our marriage since before Good Bones went viral, but more and more requests were coming in to my speakers agency because of that poem. I’d spend two days here, four days there, and a couple of times a year I’d be gone for a week-long workshop, but the bulk of my time was spent at home.

An invitation to give a reading or attend a conference or book festival meant I wouldn’t be available. Even if I arranged after-school playdates for the kids, even if I planned for my parents to be available until he arrived home from work, who would pack the school lunches? Who would drop them off in the morning? Who was going to make sure the favourite pyjamas were clean for “pj and stuffy day” at school? And – always a fear – what if one of them ran a fever and couldn’t go to school? This was “extra work” for him – and extra emotional labour, too – because, as the self-employed parent, I’d always handled these things. And, meanwhile, what would I be doing for work? Reading poems, teaching workshops, going to dinners, giving talks, being interviewed in front of an audience? Maybe for business but it sure sounded a lot like pleasure.

When my husband travelled for work, I looked forward to his return – especially if the kids were sick or I had multiple deadlines of my own – but the daily fires were ones I was used to putting out myself. On the other hand, when I would call home from a trip, I remember feeling that I was in trouble. I’d made his life more difficult, and I might pay for that with the silent treatment or a cold reception when I returned home. No: how was your trip? No: congratulations or glad it went well or I missed you. I didn’t feel missed as a person, I felt missed as staff. My invisible labour was made painfully visible when I left the house. I was needed back in my post.

It’s a mistake to think of one’s life as plot, but there’s foreshadowing everywhere. When my husband introduced me at the release party for my second book of poems, The Well Speaks of Its Own Poison, in 2015, I was standing off to the side of the stage, my arm around our daughter, holding her close. As he said many kind things about me, I remember thinking, huh. What he said about me and my writing in public felt different from his attitude at home.

Now I think of us in that room, with all of those people watching. He’s so proud of her, some of them probably thought. They’re so happy together.

In the beginning I told no one about the postcard. I wanted to save my marriage, but I wanted to save it without anyone knowing it needed saving. That is some serious first-born daughter energy right there.

We started marriage counselling about a month after I found the postcard. I didn’t tell the counsellor about it, as if not saying it aloud could keep it in the realm of the not-quite-real. The addressee wasn’t the problem, after all, right? She was a symptom. So what was the problem? My work was the problem. I was the problem – my travelling for readings, workshops, conferences. That wasn’t the deal, though I didn’t know we’d had a deal.

Before we were a couple, my husband and I became friends in a creative writing workshop at university. I think that fact communicates some of the tension in our marriage, particularly in the last years. I was working as a writer and editor; he was working as an attorney. When I got good news related to my writing – a publication, a grant, an invitation – I sensed him wince inwardly. So I stopped sharing good news. I made myself small, folded myself up origami tight. I cancelled or declined upcoming events: See, I’ll do anything to make this marriage work.

What would I have done to save my marriage? I would have abandoned myself, and I did, for a time. I would have done it for longer if he’d let me.

After we returned home from our last family vacation, we sat side by side in the marriage counsellor’s office. His narrative: we had gone to the beach with our kids, and I never played in the waves with the family.

My perspective: never was hyperbole. Rarely is true.

What I said: “I didn’t want to be near him. I was too sad.”

What I didn’t say: I thought about dying all the time. Or, not dying, but disappearing. Poof. I didn’t want to die, not really, but I wanted relief. I wanted to stop feeling what I was feeling. I carried all of that with me to the coast, and I didn’t know what to do with it there.

The sticking point: I wrote poems at the ocean and didn’t play in the waves.

The marriage counsellor said: “It isn’t about the waves.”

What I said: “He knows I’ve never liked being in the ocean much. Even before we had kids, I mostly sat in my beach chair and read or wrote.”

What I didn’t say: I wrote poems at the beach because I needed to make something more than sadness.

What I didn’t say: I’m adding my sadness to the list of things we’ll never get the sand out of. Like anything you take to the beach, it’ll be gritty for ever.

after newsletter promotion

A few weeks later, I was sitting on the left side of the couch looking at the marriage counsellor, sensing my husband’s tense presence to my right. I didn’t know it yet, but it was our last counselling session together. I summoned my courage.

“I’ve been thinking, and I need to say something.” Deep breath. “Why has this been all about him? What makes him happy. What he needs. What about what I need to be happy?”

I can’t be certain, but I swear I saw something like relief on the counsellor’s face.

Looking back on that afternoon, I put myself in her shoes. What would it be like to have a couple come in to see me, and their immediate crisis is this: the man doesn’t want the woman to continue travelling for her work, but he’s going to keep travelling for his. What would it be like to watch the woman frantically agree to try to appease her husband? Would this imbalance of power trouble me? Would I expect their “plan” to fail? If the answers are yes and yes, then a look of relief would make sense, but I’ll never be sure.

That day in the marriage counsellor’s office, I came clean. I finally told her everything. I finally admitted to myself what I’d been trying to avoid: I couldn’t be the person – or the writer, or the mother – I wanted to be in my marriage. The “deal” wasn’t working.

Walking home from that session, I knew. We’d separate, definitely. Divorce, maybe. He’d get his own place, at least for a while. We’d have the family talk that breaks kids’ hearts. I’d been trying to save the marriage, but I needed to save myself.

A few months after my husband moved out of the house, I was trying to calm and reassure my son, then six years old, at bedtime. He said: “I know, I know. I have a mom who loves me, and I have a dad who loves me. But I don’t have a family.”

I felt the wind go out of me – felt myself emptying, falling, a balloon drifting down from the ceiling – because he was right. He still had all of his family members, but our family unit, our foursome, was gone.

When people asked how the children were doing, I told them fine. It was mostly true. I told them I was grateful at least that the children didn’t lose anyone. They still have their parents and they have each other. What I didn’t say is when I lost my family, I lost someone. The person I’d called my person. In this way, my house is haunted.

There is so much I’d wish to undo. I imagine it, cinematic: I’m putting the postcard back into my husband’s work bag, and then his hand is taking it out. Then he’s unwriting it, his handwriting disappearing letter by letter from the blank side. And then he’s back in the shop where he bought it, putting it back on the carousel of postcards, and he’s walking out of the shop backwards.

Over and over again I see it, like a film. I’m pulling my hands from the bag, walking backwards away from where it sat on the dining room chair, sitting back down on the couch again.

But the undoing can’t stop there.

I’d have to keep going, to reverse everything that happened before then. Reverse through the business trips, the viral poem, the second book, the second miscarriage, the second law firm, the first miscarriage, the second bout of postpartum depression, the second child, the first law firm, the first bout of postpartum depression, the first child, law school, grad school.

There is so much undoing that needs to happen. By the time my hand slipped into the bag, so much had already happened. Too much, maybe. There is so much I would wish to undo, if I could go back. But back to where? Where was it safe?

“Do you think you’ll get married again?” People ask this – well-meaning people, people who want me to be settled and happy – and I’m not sure how to answer. – I could say I’ve promised my children no changes. That one night, tucking my daughter in, lying in bed in the dark beside her, I promised her that no one is moving in, and no one is moving out. I could say that what the kids need now is stability and consistency. They’ve had no power in how their lives are being shaped. They’ve been told where they will live and when and with whom. I understand, because I only have so much power myself. So I decided to be as constant as I can. I decided to bore the hell out of them with my same-old-same-old love. I could say that, yes, it’s sometimes lonely doing it on my own. But feeling lonely when you’re with your partner is worse than being alone. Being with someone who doesn’t want the best for you is worse than being alone. I could say that when I think about my dream partner, what I want in that person is so basic, so low-bar, I’m almost ashamed to say it out loud: someone who’s happy to see me. Someone who smiles when I walk into a room. Someone who can be happy with me and for me –

“I don’t know. It’s possible. If life has taught me anything, it’s that anything’s possible.” Next question.