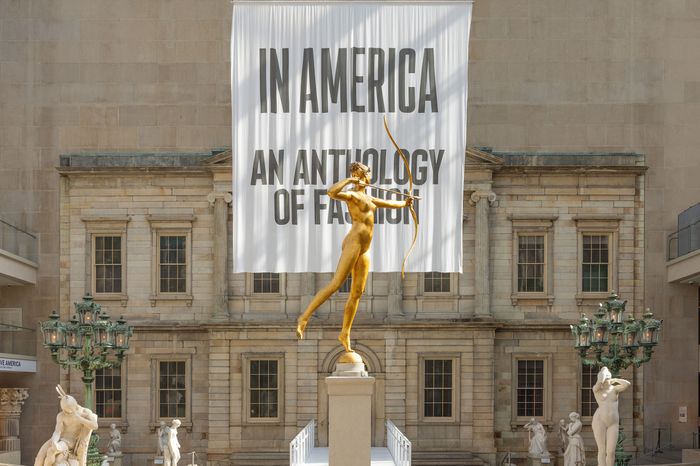

Over 198,000 visitors and counting have walked through In America: An Anthology of Fashion at the Metropolitan Museum of Art this summer. The exhibit, a challenging exploration of American fashion from the early-19th to the late-20th centuries, is mainly centered in the museum’s American Wing as a series of “period rooms,” each with distinct historic American décor. Most notable is that for the first time in the Costume Institute’s till-now homogeneous history, four Black women artists — Radha Blank, Janicza Bravo, Regina King, and Julie Dash — were asked to showcase their work.

The Met tapped nine directors in all — including Martin Scorsese, Tom Ford, Sofia Coppola, Autumn de Wilde, and Chloe Zhao — to create video vignettes that challenged or highlighted an era in fashion that was scarred by colonialism, slavery, and racism. And what the four Black women have been tasked with revealing is remarkable.

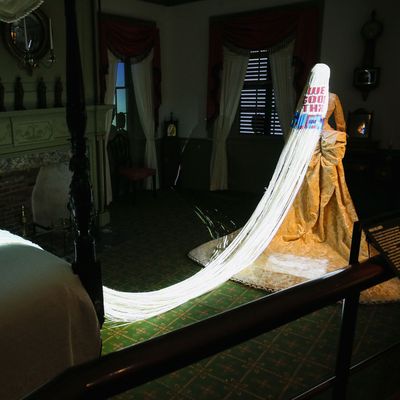

All the directors were asked to create fictional cinematic vignettes in the period rooms with the intention of reimagining a perspective on American fashion by working with historical items of clothing from the institute’s vast collection. Radha Blank’s installation, We Good. Thx! — a quilt like headpiece made with African braiding and beading techniques — explores the power of Black women’s labor and resilience. Janicza Bravo shows video excerpts from the 1970s film The Conformist and the 1930s film Ten Minutes to Live. Regina King enlisted Amanda Gorman and Steve Harris to read “& So” and “Call Us,” from her poetry collection Call Us What We Carry. Julie Dash highlights two Black fashion icons by showcasing mannequins wearing dresses by couturiere Ann Lowe, as well as a mannequin fashioned to look like actress Eartha Kitt. The exhibit is open through September 5. We chatted with Dash, Bravo and Blank. (We respectfully note that King was not available for interviews.)

What’s your favorite childhood memory of the Met?

Dash: My sixth-grade class took a bus to the Met. It had clean lines, was spacious. Lots of wonder there. I bought my mother a postcard of a Rembrandt.

Bravo: My earliest memory is from high school: I was a teenager and there with a class. The earliest kind of memory around it is some fantasy of being able to sleep there, right? Being able to be there when no one is there. It was super-surreal.

Blank: My mother made a point of bringing us to museums — the Museum of Natural History, El Museo del Barrio, the Museum of the City of New York, the Guggenheim, the Met — these were all my childhood haunts. At the Met, I just remember being kind of pulled by my mother and passing these huge relics of the past. And she would let me know that some of the pieces may have been taken from the Indigenous, explaining the origin of the artwork.

Given that it’s an institution of American art — how would you define yourselves American artists?

Dash: I am an artist who is an African American woman and a mother, who likes to challenge herself by engaging in conversation. I like borrowing from the poets, taking a simple line of dialogue — using visual metaphor and visual rhetoric in ways that perhaps are familiar but have not been visualized quite that way before. I feel that as an American and a filmmaker, I always want to place my work within an international context. I want to be in conversation with the broader world, not just a narrow urban one.

Bravo: How would I define myself as an artist? I don’t know that I ever have.

Blank: I’m an artist and I’m an American. Both of those identities are very intricately woven — heavily defined and influenced by my Blackness. I am a Black person. I’m always going to be a Black person. I never want to transcend my race; my racial identity informs everything I do. And that’s not always a good thing. I mean, it informs an interaction with a cabdriver or getting a cab in the first place. Always on guard. Always on alert. I don’t know that it always serves my sense of freedom because I’m always having to walk in that and approach everything as a Black person.

Virgil Abloh once said, “Everything I do is for the 17-year-old version of myself.” Which I think about a lot. How would you describe your installations to young people of color?

Dash: To be honest with you, I didn’t know what they were talking about when they first called. I like to be challenged. The notion of it was daunting. With fashion designer Ann Lowe, I immediately saw an opportunity to not only celebrate and elevate her work but also be a little subversive. If she was society’s best-kept secret, well, why didn’t she get her flowers while she was alive?

Bravo: I approached the assignment like I was creating a film still. It was a moment inside of a moment inside of a movie. I was thinking about it like a film still, like a tableau, like a diorama. I lately have been making work for that young self, making work that that 17-year-old wishes she’d had the chance to see. Because it took me a long time to arrive at being a filmmaker for a good deal of reasons. I needed to be able to see that someone else could imagine that I might. I’m really aware right now that there is likely someone else who needs that.

Blank: It’s about inserting Black women’s voices, in particular, back into the conversation about their own survival and freedom. Maria Hollander (the designer of the dress) was an abolitionist and a suffragette. It’s very likely it was a Black woman who helped to sew her dresses. What kind of Black woman could live in that time, survive those times? It was a kind of woman who by day is sewing dresses or cleaning white people’s homes and looking after their children and at night is kind of conjuring spells of survival and protection. The Obeah woman. The Black woman.

On the Met’s red carpet, I was wearing a phantom red-and-white head wrap inspired by the famous oil painting of Marie Laveau. I was also wearing a blue denim jacket that was inspired by the first denim makers — the indigo farmers in the south, the Geechee in the Gullah Islands. My hands were dyed blue to kind of represent them. And then I wore a dress that was white, off-white, and cream in the spirit of the ancestral clothing — the ceremonial clothing of women in Brazil or here in America.

In the installation I created, the words “We Good, Thx!” are on a cotton headpiece that accompanies Hollander’s dress. That cotton becomes the crown. It’s a textile; our experience is textured. That’s why, at some point, you see the braids are kind of growing out of this fabric form. I think of Black women braiding hair. We make quilts every day. I knew I wanted the braids to speak to this quilt. Because it’s braids, it’s immediately a Black woman because it’s a signifier of Black female. Braiding hair is survival.

What is the significance of the four Black women in the exhibition?

Bravo: It was pretty radical to be able to see there were nine directors in this show and we’re all so different. It’s so exciting; it really is. You have nine directors, and four of them are Black women? You know that never happens, right? When I saw Radha’s piece, my jaw dropped. I was like, Bravo. Just alone clapping. If we were looking at a kind of lineage, if not for Julie, there wouldn’t be myself in this space, Radha in this space, Regina in this space. And that … that felt really radical — because our work isn’t existing in the same tonal space.

Blank: Unless it’s a solely Black film festival, Black filmmakers being curated or programmed together does not happen. This is historic, and you couldn’t have a more diverse group of Black women. And so it means a lot that these four very distinct voices and storytellers are together; nothing we do is similar. But the fact that I get to share a space with Julie Dash? I don’t think anyone can surmise what she means to me in terms of having a career as a young woman. The first time I could look at a Black woman and say, “Oh, director — that’s what it could look like,” you know? When I saw Julie’s piece, I wept. I felt seen. And, I didn’t know that I needed to see that. And for Regina King, the fact that she wanted more for herself as a storyteller means she’s helping to create more texture and color in the zeitgeist, in the landscape of storytelling. And we need her. We really, really need her.

Dash: To be in a larger conversation, every room offered something different. The rooms were just there before, but they weren’t alive.