Doing the Most is a special series about ambition — how we define it, harness it, and conquer it.

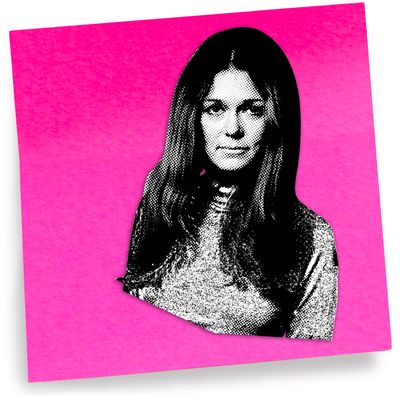

At 85, Gloria Steinem — feminist icon, author, activist, and journalist — is as prolific as ever. But in her 20s, she was just like many other writers in New York, hoping to find enough work to make rent. After establishing her career in the 1960s, she co-founded Ms. magazine, the trailblazing feminist publication, in 1971. For the next 40 years, she was on a plane almost every week, speaking and organizing at rallies and campuses around the world. Today, she continues to advocate for gender equality, and recently published a new collection of quotes, The Truth Will Set You Free, But First It Will Piss You Off! Here, she talks about her early ambitions, learning to prioritize, and how she has pushed through insults and setbacks throughout her career.

When did you start to think of yourself as an ambitious person?

It took a long time for me to feel that word was okay to use. I hope less so now, but for many years, an ambitious man was a good thing, and an ambitious woman had a hint of subterfuge, or using sexual wiles, or other not admirable traits. Even now, an “ambitious woman” sounds suspect, don’t you think?

I don’t think so, personally.

Well, I hope not. That’s good news. I’m glad to hear that.

You must have known that you wanted to accomplish big things, though, even if you didn’t think of yourself as ambitious.

As a little girl, before gender hit, I knew I wanted to be a writer. That had to do with loving books and also feeling that writing was accessible. Everybody can pick up a pen or a pencil. I was in love with Louisa May Alcott, about whom I read everything I could find, so I knew the great sacrifices that she had made to be a writer; she had very little companionship. As I grew up, and after college, I really didn’t see many women who were making a living as writers. It wasn’t until I had lived in India for a couple of years that I was able to do it myself. I was on a fellowship for a year, and then the second year, I was making a living as a writer. That gave me the idea that it was possible, and that I would try to do it when I came home.

Do you remember what you hoped to do with your writing, besides pay your bills?

That’s a good question. What on Earth was I thinking then? After I’d lived in India, I had many things I wanted to write about, so it was no longer a big generality, like becoming a journalist or becoming a novelist. It had more specificity, and that helped to make it more practical. It had substance. Without the content, writing doesn’t have a path. You don’t know how to get there. But I do remember when I began to refer to myself as a writer, and what a revolution that was. It was when I was freelance writing for magazines in my twenties and thirties, living in New York and paying the rent — a tiny rent, but still rent nonetheless — with what I earned. I needed the reality to come about before I could make the statement.

How much of your identity was based on what people said about your writing?

I took a writing class in college, and at one point I turned in some assignment and it came back with a note on the top that said, “You write so easily and well, you really should think of doing something with it.” I went up to the professor and said, “What do you mean ‘easily’?” He said, “Okay, that’s it. You’re a writer.” I’m not a fast writer, and of course it’s not easy. But it’s the only thing that when I’m doing it, I don’t think I should be doing something else. And precisely because it matters to me, then I worry about it and fuss about it and rewrite.

When you were first writing for magazines, it was really a boys’ club, at least for the kind of journalism you were doing. It couldn’t have been easy to break into — how did you do it?

I had the early good luck of being assigned by Esquire to write about the contraceptive pill, which was then new. The piece took a lot of research and work. Then my next notable piece of writing was an exposé [a two-part essay for Show magazine] about being a Playboy Bunny, and that was a very mixed blessing, to put it mildly. It was worthwhile because it did change the working conditions of the women who worked [at the Playboy Club], which were otherwise terrible and exploitative. It didn’t change them enough, mind you; it changed them somewhat. But that piece also began to dictate the kinds of assignments I got. Would I like to pretend to be a hooker? And so on. That was difficult. I imagined myself as Lillian Ross because I admired her very much and she had a great gift for observation. But because being a Bunny is based on appearance, then the question of appearance began to subsume writing in the public response.

There’s a somewhat famous story about Gay Talese making a dismissive remark that you were “this year’s pretty girl” in journalism. How did you deal with that kind of disparagement?

Poorly, because I didn’t object at the moment, which I should have. It was only afterwards that I thought, This is outrageous. I should’ve objected at the time, especially because the other person present was Saul Bellow and I had just done a profile of him, which he liked, so I might’ve had support if I spoke up for myself.

I knew that I was going to continue no matter what, but the reception of what I was doing was something I couldn’t control. I could only choose among the assignments that I could get. Which helped somewhat, because I didn’t have to take the ones that were about fashion and beauty, which are perfectly good subjects but not ones I knew about or was interested in.

Did you ever have a period where you were really discouraged about where your work was going and questioned your profession or direction?

You have to remember that, generationally speaking, we were thinking of ourselves as temporary, because we had been so convinced that we would have to get married and have children and that would become our main source of identity. I used to say things like, “Well, being a writer is a good profession for a woman because she can write at home in between taking care of children.” It was so much part of the culture that it was difficult not to think that. It wasn’t until I was in my forties that I realized, Wait a minute. This is not temporary. This is my life. I think it was a combination of supporting myself for some time, and having more companionship because there were more women writers, and just realizing that I didn’t want to do anything else.

What have you turned down so that you could focus on your work?

I once was hired to edit a regional magazine that came in the back of McCall’s. I was contentedly doing this two days a week at home, assigning other writers, when a new editor of McCall’s arrived, a male editor, and he had the nerve to expect me to be in the office two days a week. I quit because I just didn’t want to be in an office doing other people’s work. I wanted to be at home at my desk doing my own writing. It was perhaps unreasonable and irrational of me, but it was instinctive. I think I was also influenced by my father, who was very proud of never working in an office. He did freelance things, like selling antiques. He even had a summer resort for a while. His point of pride was he never worked for anybody else.

I also learned from other advocates around me that when you’re doing what you love and care about, it’s not so evident to you that you could be leading a more peaceful life or making more money, because that would be boring. You’re going towards interest and excitement and feeling an urgency about what could be done. It’s a choice, but it doesn’t feel like a choice.

How do you split your energy and time between activism and writing now?

If I am hoping to do a longer writing project, a long essay or certainly a book, then I have to take time off from other activist projects. But that’s difficult. I signed the contract for my book, My Life on the Road, 20 years before I delivered it — so, I rest my case. Also, writing is probably always part of my activism because I’m striving to create phrases that are activating, or write op-eds or even just emails explaining the necessity for raising money for whatever form activism is taking.

It’s an unfortunate truth that we tend to think we’re immortal, but I’m trying to remember that I’m not at my age. I say to myself, All right, here are the several things that you really want to do, and I need to do them now. This is difficult because every day there are organizing opportunities or emergencies or requests or communal projects that I’m involved with. So I’m not saying that I’m very good about prioritizing, but I do recognize that I need to do it.

Do you think you hold other people to the same standards that you hold yourself?

God, I hope not, no. But helping your friends follow their ambitions is very satisfying. I’m sure you have this experience: Your friend says something to you and you say, “That’s it. That’s a great idea. Why don’t you write that?” or “That’s a great title,” or, “We need to know that. That should be an op-ed. That should be a whole book.” Not that my friends always listen to me, but hearing something that’s new and exciting and important is a gift in itself, so you want to support it. You want that person to do more.

What makes you feel like your work has been worthwhile?

The moments that come to mind are people coming up to me in the street or the airport or a restaurant or a demonstration, people I don’t know, who say to me that something that I wrote was important to them or had an impact or gave them an idea of what they could do. That is absolutely the most satisfying feeling, way more satisfying than money. Not that we shouldn’t be paid fairly, mind you, but in terms of satisfaction, that is, by far, the biggest gift.